My father Elmer—a rather odd moniker for a Jewish kid from Pawtucket, Rhode Island—taught Shakespeare at Brown University for almost 40 years. But he could quote Harpo as easily as Hamlet, Philip Marlowe as easily as Christopher Marlowe. A good line was a good line. Provenance had little to do with it. He was an exacting grammarian who would repeatedly remind anyone within earshot that “the reason is because” is redundant…ditto for “proactive,” and that you shouldn’t start a sentence with “hopefully” (no matter what anyone else said). But he also suggested that beginning sentences with conjunctions was permissible if done sparingly; it was OK to occasionally split infinitives and end sentences with prepositions if you needed to. Sentence fragments were also OK. In moderation. If you catch my drift. Rules were meant to be broken but only if you knew you were breaking them and had a damn good reason for doing so. It was more important for you to have command of the language than for it to have command of you.

My father Elmer—a rather odd moniker for a Jewish kid from Pawtucket, Rhode Island—taught Shakespeare at Brown University for almost 40 years. But he could quote Harpo as easily as Hamlet, Philip Marlowe as easily as Christopher Marlowe. A good line was a good line. Provenance had little to do with it. He was an exacting grammarian who would repeatedly remind anyone within earshot that “the reason is because” is redundant…ditto for “proactive,” and that you shouldn’t start a sentence with “hopefully” (no matter what anyone else said). But he also suggested that beginning sentences with conjunctions was permissible if done sparingly; it was OK to occasionally split infinitives and end sentences with prepositions if you needed to. Sentence fragments were also OK. In moderation. If you catch my drift. Rules were meant to be broken but only if you knew you were breaking them and had a damn good reason for doing so. It was more important for you to have command of the language than for it to have command of you.

Elmer taught me the crucial difference between what I thought my words were saying and what they actually said. In the former, writers really only listen to themselves, leaving the reader to watch from a distance as phrases and sentences careen unchallenged around the writer’s brain, trapped in self-referential loops. In the latter, the writer listens along with the readers. They may not agree. They may not even like each other. But they are at least on the same page.

In 1967, I wrote an impassioned essay for my high-school paper looking at the brutal massacres of Vietnam citizens in light of the Nuremberg Trials. Elmer agreed with the sentiment, but pointed out that since the piece was riddled with false equivalencies and tenuous logic, it would be hard for the reader to fully appreciate the righteous passion behind it. I stormed away in frustration, of course. Three years later, he tried to convince me to apply the same discipline to a paper I wrote arguing that many biblical visions were drug-induced hallucinations. He suggested that my “brilliant” insights wouldn’t be taken seriously if I kept jumping to so many equally drug-addled conclusions.

One of the more misguided flaws of my generation was the assumption—particularly when hallucinogenics were involved—that you had to be there. A reader has never had to be there. Otherwise, there’d be no science fiction. Not to mention One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. These days, I often think of Elmer when I’m reading emails and texts. It’s a good thing that he shuffled off his mortal coil almost 30 years ago. While he might have considered emoticons a mildly amusing use of keyboard letters and symbols, he would have considered emojis an abomination (one of his favorite words). Even now I can’t use them for fear he’ll come back and smite me. I mean this was a guy who said if you had to use an exclamation point your words weren’t strong enough!!!!! To use a deranged smiley face with sparks flying out of its head would be something up with which he would not put(!)

]]> Pockets are a problem. Whoever came up with the idea back in 18th Century England was doing too much snuff. Pockets are especially a problem for writers. Because, in addition to keys, loose change, wallet, eyeglass case, and cell phone, you also need a pad, pen, pencil, glasses, and, of course, a napkin that you’ll throw away even though it has some really good ideas on it. (Not to mention masks. Two years ago it was hard to find one. Now they appear in the pockets of every coat I put on.)

Pockets are a problem. Whoever came up with the idea back in 18th Century England was doing too much snuff. Pockets are especially a problem for writers. Because, in addition to keys, loose change, wallet, eyeglass case, and cell phone, you also need a pad, pen, pencil, glasses, and, of course, a napkin that you’ll throw away even though it has some really good ideas on it. (Not to mention masks. Two years ago it was hard to find one. Now they appear in the pockets of every coat I put on.)

Admittedly, I make things worse by dressing in layers—an increasing number of layers as it gets colder. So, between jeans, fleece vest, sweatshirt, and the occasional windbreaker, I could be walking around with anywhere from five to ten pockets. And I’m not even counting those weird hidden zippered ones. You put something in one of those and it’s history.

All those pockets, combined with a barely detectable attention span, mean it’s unlikely I’ll find my phone before the person hangs up, a pen before I remember what I wanted to write, or my keys anytime in the near future. So I end up spending most of my time in public patting myself in ways that many people would find disturbing.

For several years, my wife Wendy would mildly suggest—and that’s putting it mildly—that I put myself out of my misery by getting a “man bag”. In addition to the phrase’s troubling connotations, I didn’t see how I’d benefit from a public display of pockets. Besides, I’ve known people who have spent half their lives looking for the perfect handbag and the other half trying to find the things they put in them. Me? A man bag? Forget it. It’d raise a few too many eyebrows in my definitely dressed-down Vermont hometown and would give certain people way too much cynical fodder. So, it came as a surprise to both me and Wendy that, one day, when we were walking through a crowded outdoor market, I absent-mindedly tried on a few man bags and made a vaguely positive comment about one of them. Before I could object, she’d bought it.

I spent a few weeks trying to wear the thing. I successfully designated two pockets for the essentials—one for my phone and another for the pad, pen, and glasses. I didn’t even panic when I discovered two more tiny side pockets that were crying out for toothpicks, aspirin, or my 30-year-old Swiss Army Knife that would get confiscated at the airport because I forgot it was in there. I was almost starting to get used to wearing it until I met our daughter for lunch a week or two later. Emily has the same acute design eye as Wendy, albeit with a different generational aesthetic.

“Look, Em…Mom finally got me to buy a man bag,” I said, bravely flinging it over my shoulder. She tried not to blink. She wanted to be supportive of my new fashion statement, but her hesitation said it all.

“Not working is it?” I said quickly.

“It’s just…”

“No, I totally agree with you,” sensing this might give me a way out of this increasingly uncomfortable experiment.

She proceeded to make all the points above and more until she finally suggested that perhaps I needed something bigger; something more mail– than man–bag.

“Well, then I might as well just use my computer bag again,” I said hopefully.

“No, smaller than a computer bag,” she said thoughtfully.

I looked at her. She looked at me.

“It’s a problem,” she said.

]]>Waking the Dead

Peter Paul Rubens

1577 – 1640 Flanders (Belgium)

Rubens brought together the best of Italian and Dutch renaissance painting into a lush style that has become known as Baroque. His ability to bring the human form and flesh alive continues to amaze. He was also, by the way, a skilled diplomat who quietly helped maintain peace between Holland’s independent north and his own Spanish-controlled south.

“This simple and most elusive of truths surrounds us. Your enemy is that stroke of red. You are that stroke of blue. Your enemy is that stroke of white. You are that stroke of black. You complete each other.”

View Full Text

Peter Paul Rubens

Inside The Metropolitan Museum of Art, it sounds like a chorus of out-of-tune angels.

The shrieking sopranos of hormonal students clash with the annoyed baritone of aficionados and the nervous tenor of tourists. The solos of tour guides are drowned out in the din.

Maslow turns left and goes forward into the past: The blank stare of a Roman emperor. A Greek amphora paying homage to war-horses and the promise of nepenthe. A child-like Pharaoh, his family illuminated by a beneficent sun.

He turns right, walking past the modern art with his head down until he discovers America, where he speculates on the sex life of the couple who slept in that four-poster canopy bed—and the safety of the baby in the antique cradle at their feet. Glancing furtively to see where the nearest guard is, he lifts one of the exquisitely carved ivory pieces on the lacquered chessboard and moves Pawn to King 4.

He knows he’s taking a risk coming to the Met. Every object threatens to shatter the increasingly thin veil that separates their past from his present. An hour later, after pondering the inner life of a mounted knight, encased in armor, he takes refuge in the cafeteria and sips on a half-decent double latte.

Returning to the main gallery, he watches visitors ascending and descending the central staircase like angels on Jacob’s ladder. Taking a deep breath, he begins to thread his way up.

“Let’s look at the paintings…the ones to the right. It’s a special exhibition.”

The voice comes from a few steps up. A teacher leading a group. Maslow follows them into a room where he is surrounded by weighty portraits and mythic scenes in ornate gilded frames.

He sits on a cushioned bench behind the group, picking up snippets of their conversation as they look at Rubens’ Venus and Adonis:

“Look at the tension in Adonis’s muscles. The precision of his elbows, knees, and calves. The way he is reaching for and pushing Venus away at the same time. ”

“Wow, that dog’s nose…you can almost smell the woods through it!” a student

adds to appreciative nods and murmured “yesses,” “definitely’s,” “ and amazing’s.”

“The angel wings,” another student adds, sighing and shaking her head in wonder.

“Not much life left.” The voice has a touch of nostalgia but is devoid of selfpity.

Everyone’s a critic, Maslow thinks—a final pedestrian thought; the ordinary mind’s instinctive grasp for solid ground before the door swings shut behind it—a hallmark of these encounters.

“A dying myth,” the voice adds.

“He looks like a real asshole to me,” one of the students says.

“Old story,” adds another.

“Typical male wish fulfillment,” adds another to laughter all around.

“Good for them! Fresh eyes!” The voice is so loud Maslow looks around quickly. But it carries the echoes of centuries, not marble halls.

The lecturer rambles on as the students begin to drift away one by one to look at other paintings.

“You painted it, right?” Maslow whispers.

“Yes. Painted.”

He emphasizes the past tense.

“I said what I had to say then. I’m ready to say what I have to say now.”

Maslow reaches into his jacket pocket, brings out a folded piece of paper and a pencil.

The Master’s chuckle is a light rumble at the bottom of a deep cavern: “No. Not here. I need the proper tools.”

* * * * * * * * * *

The proper tools. Over the next few days, Maslow looks for hints on the streets of New York. An iconic art store in the Village where he finds powdered pigments that would seem to be right up Rubens’s alley. Another high-end store near Pratt where he lingers in front of a display of oil sticks, waiting for the Master to signal his approval. Nothing.

Thinking that maybe Rubens wants to try his hand at something more modern, Maslow goes to a mega-drugstore and stares at cheap pens, markers, and pencils of many colors.

But the artist keeps his own counsel…until, a few days later, Maslow sees a billboard on his way out of the city.

It’s a picture of a bright green way-larger-than-life Mr. Bendy-type character with a conical hat, bulging psychotic eyes, and a crazed grin, hugging a little boy and girl a little too close for Maslow’s comfort. The clearly-deranged figure invites “kids of all ages” to visit the Crayola Crayon Factory Museum in downtown Easton, Pennsylvania.

“Ahh…perfect,” Rubens sighs.

Maslow sighs too. He’d been going west on 78, hoping to make it to Harrisburg in time to have dinner with friends. Instead, he’ll be staying the night in Easton, waiting eagerly, with a bunch of six-year-olds, for the Museum to open at 10 the next morning.

He had presumed he’d be walking into a Willy-Wonka-worthy blend of industrial strangeness and magical realism. He’s half right. The Museum is a bright and shiny psychedelic showcase to the “Crayola Experience,” a place where the operative compound adjectives are “multi-colored,” “larger-than-life,” and “handson.”

The air is not so delicately fragranced with a pervasive Eau de crayon that waxes and wanes from room to room.

The factory itself is at an undisclosed location several miles away, where lawyers don’t have to worry about children falling into vats of molten wax.

Rubens doesn’t seem concerned with the sleight of hand.

“Fabulous. Absolutely fabulous.”

At the Met, Rubens was dismissive. Here he is enthralled.

“Let’s take a stroll, shall we?”

First, they stare with childlike fascination at The World’s Largest Crayon. It’s True Blue, 15’ long, 16” in diameter, weighs 1,500 pounds, and is made from 123,000 blue Crayola crayon nubs contributed by kids from all over the country.

“I wonder,” the artist muses but doesn’t elaborate.

They watch a demonstration of a “real” crayon-making machine. Next to the machine is a display that keeps a running tally of how many Crayola crayons have been made in history—more than 150 billion, and somehow still counting.

Rubens shakes his head. “Why blend so many colors in advance?” He’s mystified.

As they continue their self-guided tour, Maslow feels increasingly invisible and conspicuous at the same time. He’s not the only grownup there. But he’s the only grownup who isn’t either working or accompanied by a child under the age of ten.

He imagines the elderly volunteers, who wear Jazzberry Jam shirts under official looking Black or Outer Space aprons, tend to keep a close eye on middle-aged guys wandering around and mumbling to themselves.

Suddenly a jester approaches wearing a hula skirt made from strips of crayon colored cloth that swish around his khaki pants and sneakers. His jersey is a tie dyed Midnight Blue with large Laser Lemon circles on a field of good-old reliable Red. He wears the same high conical hat as his doppelgnger on the billboard—shaped exactly like a crayon, made of small diamond patches of different colors.

The character bows and materializes a small box about the size of a pen and pencil set. A gift for visitors? He holds it out to Maslow’s right hand, but, as he reaches for it, the jester pulls it back and holds it out to Maslow’s left. Looking back and forth in pantomime confusion, he shrugs, gives it to Maslow, takes a quick bow, jumps in the air, clicks his heels, and dashes off.

Maslow walks over to a low railing to open the box. It’s the familiar Crayola Orange-Yellow. But it has a green wax seal on the front with the letters “PPR.”

There’s no flap. The top lifts off. It appears to be a little telescope or spyglass.

Until he looks more closely. It’s a kaleidoscope. Rubens gasps as Maslow puts it up to his eye. The colors are more spectacularly illuminated than Maslow has ever seen. Or that even the master could imagine.

The next room is full of large circular drawing tables. In the center of each, is a 4-foot diameter Ultra Yellow teacup filled with 5-foot high crayons. It looks like a stage set for Alice in Wonderland.

At the base of the giant teacup is a revolving carousel with thirty or so plastic bins filled with thirty or so different-color regular-size crayons so kids at the table can spin it around and grab the ones they need.

“What are you waiting for? Draw!”

Maslow’s head jerks up as he has a brief flashback to 2nd grade. Flashing forward, he takes a large piece of drawing paper, spins the carousel, grabs a fistful of crayons, and starts scribbling—lines, shapes, swirls, whatever.

“Behold! It’s Judgment Day!” The Master sounds as if he’s greeting a long-lost friend. “Men tumble to their deaths faces frozen in rigors of fear. Women, their bodies contorted, shield their eyes from unspeakable fates. A riot of flesh! Tortured cries. Faces etched with gashes of anguish. Lucifer himself waits with a selfsatisfied sneer!”

Maslow continues grabbing crayons at random, stroking boldly across the page, as Rubens orchestrates.

“But look above! Sweet faces of care, compassion, and hope. Confident muscles clutch the faithful. The soft curves of bodies at peace, rising towards Lord Jesus, Blessed Mary, and the saints, as angels go about their business, anointing the blessed—like bees from flower to flower.”

As Rubens talks, Maslow’s crayon-filled fists continue to fly, coating the edges of his hands in a thin film of wax.

“Now, open your eyes!”

Maslow’s eyes flash open. But he sees only scribbles.

“Ach,” the artist seems frustrated. “Soften them!”

Maslow lowers his lids as he grabs wildly at colors.

“Behold! This apocalyptic scene—hellish fires and celestial light—is, in truth, nothing more than color, shape, and shadow. To reject any part would be to reject the whole,” he sighs, speaking as much to the heavens as to Maslow.

“New sheet of paper!”

Maslow spins the carousel. A little more forcefully than necessary. He looks around…furtive…guilty. But all the other innocents are still standing or kneeling on stools, totally focused, as if reality itself depended on their ability to depict it.

Fortunately, none of them seems to mind that a grownup has been monopolizing the flesh tones. Their parents stand behind them warily. Waiting for the guy to make one false move so they can call security. Even though, at this place, Maslow thinks—relieved his ordinary mind remains somewhat intact— the sheriff would probably be Quick Draw McGraw.

He reaches for even more vibrant colors.

“Christ Lowered from the Cross,” the Master announces. “The full weight of his humanity about to tumble to earth. Celestial radiance illuminates his power.

Each brushstroke a balm for the grieving.”

He sighs as Maslow dabs streaks of Hot Magenta blood along Christ’s forearm and the wound at his side. He colors Magdalene’s cloak with Scarlet, softening it by rubbing it with his thumb. For the cross itself, he reaches for browns and yellows (Inch Worm, Desert Sand, Macaroni and Cheese), and to highlight the beard of the apostle who’s struggling to support the torsioned right shoulder of his lifeless Lord.

“Where others use Christ’s torment to stoke the fires of hatred, I stroke it gently…soothe his suffering to rest at long last…so we can move on. Many have come to earth with words of wisdom and love. But the path from mind to heart is long and arduous, filled with twists and turns. Ideals of love metamorphosing into excuses for hate.”

Rubens pauses a moment, considering his own words, and then continuing softly: “Now, imagine yourself being lowered off the cross.”

A wave of release flows through Maslow’s body as he falls under the sway of deep blues and indigos, the firm grasp of Rubens’ invisible hand, and the insistence of his voice and vision:

“Now imagine your bitterest enemy being lowered off the cross.”

Maslow gasps. A long-forgotten face comes to mind—a petty tyrant of a client whose grandiose praise barely concealed an insatiable desire to manipulate…control…crush. He envisions the man now, full-figured, naked, loinclothed…the Christ.

Oh my. Oh my.

A little girl, with predictably cherubic cheeks and carefully cropped blonde bangs, slides off her stool and catches a glimpse as she runs off to show someone her own divine drawing. “That’s pretty,” she says, pausing before skipping away.

“New piece of paper!” Rubens commands. “New Day of Judgment. Your life passes before your eyes. Everyone you know. Some fall to the fires. Others rise to the heavens.”

Family, friends, enemies, and strangers appear in Maslow’s mind’s eye, one-byone as if volunteering for bit parts in the epic.

“Now take those who were ascending and put them in the fires of hell and take those who were falling and raise them to the right hand of the Lord. Continue.

Continue. Continue!”

Maslow does as he commands. Coloring, coloring, coloring…a multitude of familiar forms and faces in various throes of finality. Minute by minute, the painting becomes more complex until he’s startled to a halt by Rubens’ voice, now soft, sad, avuncular:

“This simple and most elusive of truths surrounds us. Your enemy is that stroke of red. You are that stroke of blue. Your enemy is that stroke of white. You are that stroke of black. You complete each other.

“For, in the end, each spirit is nothing more, nor less, than an infinitely complex but extraordinarily simple swath of colors.”

Like lights slowly illuminating a darkened auditorium, Maslow becomes aware of himself. Hunched over the paper. Muscles and ligaments stretched taught across his shoulders. Hands clenching crayons. Eyes now squeezed in intense focus.

He takes a deep breath, lets his body relax, opens his eyes, and looks at all three drawings side by side.

He sees nothing but scribbles.

At that moment, the little girl comes running back.

“What’s that?” she points at the gift box, pulling him back in the general vicinity of the here and now.

“It’s called a kaleidoscope. Want to see?”

She nods, picks it up, and puts it to her eye.

“Now turn it down here, you’ll see what happens.”

She does. “Wow! Neat!” She looks all around the room, turning the cylinder.

But when her eye falls on Maslow’s three drawings, she stops, takes the

kaleidoscope away from her eye, looks at the scribbles, and then puts it back. And then away. Back and forth a few times. She turns to him with wide eyes and a mischievous smile, like he did a magic trick that she really really wants to be magic even though she knows it’s just a trick.

She starts to hand the kaleidoscope back to him but pauses.

“Could I?”

Maslow hesitates but… “OK. Just let me look through it first. I haven’t even tried it yet.”

She nods enthusiastically.

He takes it and, imitating her actions, looks all around the room ending up at his three scribbled drawings. Now it’s his eyes that grow wide. He takes the kaleidoscope away from his eye. Puts it back. Then away. A few times.

He’s barely aware of handing it to her.

“Thanks!” she says enthusiastically, running off with it.

Maslow slowly and deliberately gathers his three masterpieces and walks quietly to the exit, careful not to break the spell.

Staring.

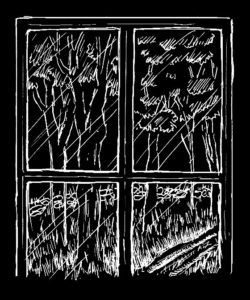

For me, staring is a critical part of the creative process. It’s like a meditation except that the rules (actually, non-rules) are to let yourself follow any promising thought that appears in your mind’s eye—as opposed to the “serious” business of following your breath (trust me, it ain’t going anywhere…)

Trees have always been my go-to staring non-object. These days, it’s the swaths of hard and softwoods marching in formation across Mount Wantastiquet (Atowi: Wantastegok Wojo) on the other side of the Connecticut River, or the oaks creating a canopy over Lake Dunmore. (My go-to Abenaki expert says the Native American source of the lake name is elusive.) At other times and places it’s been a row of maples above a steep bank, a single tree in front of an office window, or a whole peach orchard outside a screened-in porch. (Interesting that it’s easier to remember what I stared at more than what I wrote.)

The other day, I got curious about what happens in your brain when you stare. I had images of calming dopamine and happy-go-lucky serotonin molecules zooming around through wide-open neural pathways, leaping headlong into the receptive axons, triggering a brilliant new idea here and then another one there. A cluster f—k of exuberant synapses.

Imagine my concern, if not outright horror, when my quick search yielded references to something called “absence seizures,” a childhood condition caused by “abnormal brain activity” which is, of course, my favorite kind. During one of these seizures, kids will suddenly stop doing what they are doing, their eyelids may flutter, and they might not respond when spoken to (which, I thought, is pretty much what kids do anyway.)

NB: These little “seizures are usually not super serious but people who know a lot more about kids’ brain health than I do say they may be worth checking out.

Creatively productive staring has become harder in the 21st Century now that all human knowledge is at your fingertips. Just when the ideas are starting to float untethered before your mind’s eye, you convince yourself that you immediately have to find out how much stronger fentanyl is than morphine (about 100x depending on the purity); who’s really buried in Grant’s tomb (nobody—he’s in an above-ground sarcophagus); or whether it’s going to snow on Friday (80% chance).

Once you pick up your iPhone to find answers to questions like these, your staring session is essentially over. You might as well open your laptop and put your nose to the grindstone (which refers to millers leaning over to smell whether the stone is getting so hot it’ll scorch the flour).

Don’t worry. Soon, you’ll have another chance to settle back, look out the window, and stare. If you’re lucky you might get to see what Wendy saw as a child.

]]>When I need a nap, any place will do. I can lie down on a bench, office floor, tilted-back car seat, couch, or even under a bush, and doze off for a half-hour, regardless of background noise or distractions.

Napping is one of my most valuable writing tools—right up there with laptops, pens, pads, scraps of paper with indecipherable scrawls, backs of envelopes, walks in the woods, bike rides, toothpicks, Wikipedia (yeah, I confess), tea, coffee, wine, and a little Adderall when nothing else works or, well, if truth be told, I just feel like it.

With a nap, you get two days of writing in one. After 30 minutes or so, you wake up, stagger around just like you did that morning, make a cup of tea, and stare blankly out the window. Inevitably, if you’re patient, ideas will start floating up from your subconscious…which has been trying to get your attention all day.

Then, all you have to do is open your laptop and—here’s the hardest part—write those rough phrases and sentences down before checking the weather, e-mail, Facebook, Instagram, CNN, or indulge in any of a number of random activities that could easily wait until later.

If you do get distracted it’s no big deal. Self-flagellation is the biggest distraction of all.

]]>

(Many years ago, I was interviewing a CEO so I could ghost write his annual report message. He explained that their strategy was to “leverage their core competency to maximize their operational return.” I said, you mean you’re going to “do what you do best to make money?” He was not amused. But I was.)

At some point when I wasn’t looking, the clunky, consonant-riddled word “haptic”—which has nothing to do with being happy or ticks—started appearing in System Settings for phones and computers. It’s a word that only a linguistically passive-aggressive techno-geek could love. The kind of word that people make up when they want to convince people that they are thinking or doing something important. Like “pivot,” “leverage,” or “core competency.”

(Many years ago, I was interviewing a CEO so I could ghostwrite his annual report. He explained that the company’s strategy was to “leverage their core competencies to maximize their operational return.” I said, you mean you’re going to do what you do best to make money? He was not amused. But I was.)

My adventures in “haptic-ing” [definition at the end] began when I was given a Smith Corona Electric typewriter by my parents on my Bar Mitzvah. The symbolism of getting it on the day I allegedly “became a man” doesn’t escape me.

The second most important gift I got that day was a touch-typing course that consisted of several 33-rpm records and a manual. “A,” the record would say. “A” “A” “A” “A”… I could have obeyed its commands all day. And, for many days I did until I could type 30, 40, and eventually 70-80 words a minute. But the real accomplishment wasn’t speed; it was discovering that I could have a direct connection between my brain and fingertips. From then on, while the words might not always come easily, the actual “writing” could be seamless—without the distractions of pencil sharpening, left-handed smudging, and trying to write in a straight line. All I had to do was change the ribbon once in a while and use a pin to pick out the ink that had hardened inside the o’s, p’s, and d’s. Since then, I’ve worked at a keyboard virtually every day. Let’s call it ±55 years. 350 days a year. Maybe two hours a day. That’s 38,500 hours. Say I’m typing a leisurely 50 words a minute. If my math is right, that’s more than 2 million minutes at the keyboard and more than 1 billion words. Give or take a few million.

Of course, I’ve erased a lot of those words: first with a nice soft pink eraser on “Corassable Bond.” Then with Liquid Paper, Ko-Rec-Type, and the ribbons that were black on top and Ko-Rec-Type below. “Delete,” “Command + X,” and “Command + Z” may be faster and cleaner but they don’t force you to make the same commitment to every word that a typewriter does.

We had a manual typewriter in the house when I was little—an Olivetti or Smith Corona. All I remember about it is banging on the keys to see how many you could jam up at the platen before your parents told you to stop.

The first typewriter I ever used for its intended purpose was my dad’s Smith-Corona Electric. He said it was the very first one. Which I took to mean first on the planet, although he meant in terms of model years. I liked this machine. In fact, at some point, while I was in college, I traded him that Bar Mitzvah typewriter for it. Not only could you watch the action like on a manual, but it also had the old-fashioned manual return. The very way you hit that lever and threw the carriage back told volumes about who you were—as a person as well as a writer.

By then, the pinnacle of typewriter technology was the IBM Selectric. They were way too expensive for me at the time, but somehow I got a hand-me-down in the late ‘70s. The only problem was that watching the ball spin around was much more interesting than writing. More problematically, it let writers change typefaces—beginning the process, which has only escalated exponentially since then, of being able to distract ourselves from the work at hand by screwing around with formats.

My first real foray into computers was in January 1984. The keyboards weren’t all that different from the ones on electric typewriters. But the change, from looking at the paper on a platen to looking at a screen, short-circuited the critical brain-fingers-words feedback loop that had subconsciously become a core component of my writing process.

Fortunately, once I got used to it, the quieter and more sensitive computer keyboards made that loop even more seamless—although the need to use a mouse (back then) and eventually a trackpad took some haptical getting used to. I still prefer trackpads because it’s easier to keep one hand positioned correctly on the keyboard as I’ve been doing, well, since my Bar Mitzvah…

Which brings us, at last, to the definition of “haptic”: a technology that uses touch to control and interact with computers. (If it sounds Greek to you, it’s probably because it’s derived from the Greek haptesthai, meaning “to touch.”)

I’ll probably always refer to “touch and feel” rather than haptic. It doesn’t matter. No matter how sophisticated the technology gets, the real miracle is that we can put our thoughts into words—and, at our best, throw our hearts into it.

]]> Notebooks & Pads.

Notebooks & Pads.

One of the most Quixotic quests of my writing career has been the search for the perfect notebook and/or pad. I imagine many other writers have tilted at that same elusive windmill.

I’ve used everything from dime (now dollar) store notebooks that are spiral bound at either the side or top, to journals and blank books that seem too elegant to ravage with my impatient scrawl.

Pads? Don’t get me started: Plain, lined, or even graph paper; yellow, gray, pink, blue; letter & legal size; eco-friendly and not-so; one for each project—a designation that lasts about a day; clipped to different clipboards or put into large quasi-binders with pockets, dividers, and labels on tabs that are immediately covered up by the oversize papers I shove in.

Some people claim the secret is to use one notebook for everything you want to take notes on, chronologically, until it’s filled. I’ve tried that. The battle between my creativity and futile obsession to keep things organized turned the poor thing into an illegible war zone.

I’ve tried starting from the left with my left-brain ideas and from the right with my right-brain ones. Pretty soon, I forget the difference. I never reach the center from either side, anyway. Plus I’m a lefty. Which, in terms of writing left-to-right, is a handicap that only Leonardo overcame elegantly and, even then, in a literally backhanded way.

Every few months I grab all the notebooks and pads in sight, transcribe anything I think could possibly have any value, and then tentatively throw away the remaining pages, still concerned I might have lost a good one-liner forever.

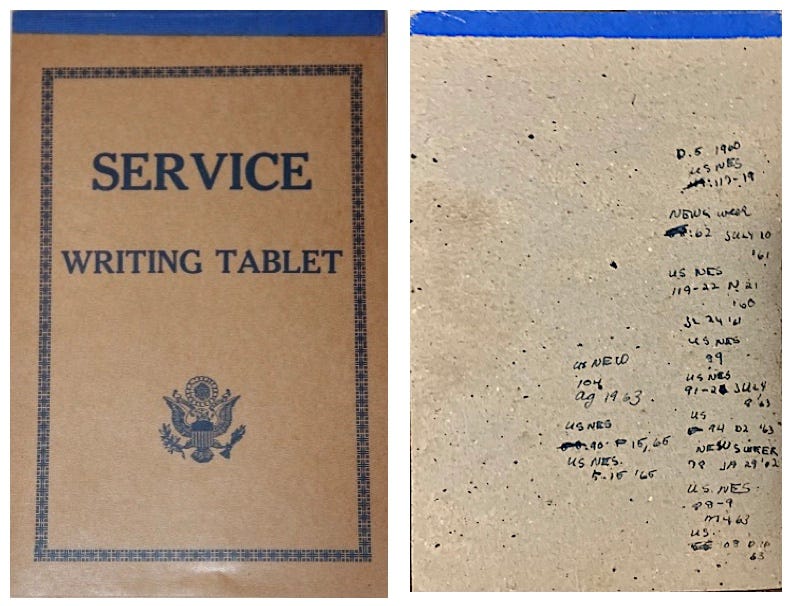

There’s something about certain pads that have been around for a while that transcends the words written on them. My favorite is the “Service Writing Tablet” that soldiers were given during World War II to write letters home (and/or their last words). Fortunately,  for my dad (and me), it was the former. He didn’t use those “tablets” much because, when his superiors found out he was an English Major, they handed him a typewriter so he could type grammatically correct reports for headquarters. It also made it possible for him to send legible letters home—many of which tried to set his family’s mind at ease by obscuring the fact that there was a war going on and he was closer to the front than he let on.

for my dad (and me), it was the former. He didn’t use those “tablets” much because, when his superiors found out he was an English Major, they handed him a typewriter so he could type grammatically correct reports for headquarters. It also made it possible for him to send legible letters home—many of which tried to set his family’s mind at ease by obscuring the fact that there was a war going on and he was closer to the front than he let on.

Somehow I ended up with one of those “Service Writing Tablets”. I’ve torn out most of the pages over the years. But, on the rough cardboard-like back, there are scribbled references for some high-school term paper that I wrote—undoubtedly while standing over a huge oak card catalog in the library.

I can still see…it’s more a feeling…the kid who wrote those notes fifty years ago. The words may now be irrelevant, but the synesthetic memories buried in that pad say a lot more than those words ever did.

Writing Asides Post Template (RENAME ME)

Lorem lorem replace replace

Waking the Dead

Elizabeth I

1533-1603 England

Through skilled diplomacy, uncommon wisdom, and unparalleled charisma, the brilliant and beloved “Virgin Queen” Elizabeth brought religious peace to England during the worst days of Protestant-Catholic conflict. And, with minor exceptions, she maintained military peace with other nations in the treacherous times during which Western European countries were incessantly vying for control of the New World…and each other. She also inspired extraordinary achievements by some of her most loyal subjects—from Sir Francis Drake to William Shakespeare.

“To stay in the presence of conflict without flinching, without reaching for the weapon, without signing the order of execution, without agreeing to the marriage takes real courage.”

View Full Text

Queen Elizabeth 1

Every Thursday from May to September, Maslow’s friend Alma serves afternoon tea at 4 pm sharp. From October through March, she serves cask-strength single malt at 5 pm sharp. Homemade oatmeal cookies with the tea. Fine cheeses and crackers with the single malt.

She takes April off. It’s planting season and she’s just too busy.

Alma has been doing this for about three decades. On her screened-in porch in warm weather. In her formal dining room when it’s cold. Usually about a half-dozen people show up. Sometimes no one does, in which case she contentedly reads a book with her cat Ramona on her lap.

“I’d like to catch a wild swarm sometime,” she says as Maslow comes in and pours some tea. She doesn’t look up. She knows it’s him. Or maybe it doesn’t matter.

Alma’s latest passion is beekeeping. In the sixty years she’s lived on this land, she’s been passionate about many things: esoteric astrology, heirloom apples, companion planting, herbal medicine, several guys, and one son but, except for him and her grandchildren— she’s left all those pursuits behind.

What began as a legendary commune in the 1960s has slowly returned to its original state—A 1780’s farmhouse on 85 acres of land. The cabins, lean-to’s, yurts, geodesic domes, and tents have all

Waking the Dead — Queen Elizabeth 1 2

disappeared or fallen into terminal disrepair, although Alma will always materialize a bed or couch for anyone who stops by. Particularly her fellow travelers.

“Why is catching a wild one so important?” Maslow asks, sliding into the middle of the conversation she’s been having with herself.

As Alma’s face has become increasingly worn, her eyes have grown only brighter. And her laugh more lovingly maniacal.

“‘Cause I like wild queens, you idiot!”

Over the next hour, Alma tells Maslow more than he ever expected to know about honeybees. By the time he leaves, his mind is swarming with queens.

********

One of the recreational hazards of living in Vermont during the Spring is the annual return of Morris dancers.

Morris dancers are a harbinger of warmer days; they make people smile; they hop around as if the sidewalk were covered with hot coals; they got rhythm (kind of); they drink lots of beer. Everyone loves them.

Except Maslow. He finds them vaguely annoying. He can’t explain why. He just does.

So when one approaches him the following Saturday, he walks faster; looks down, and acts like he’s thinking of something important:

Like how to feed the homeless, solve global warming, or end the war— any war. Those are very popular subjects in Vermont. It’s obvious he shouldn’t be disturbed.

“Semper Eadem!” an excessively cheerful guy chirps, shoving a flyer under his nose. Maslow takes it with a wan smile and puts his head back down to avoid further conversation.

He rounds the corner, crumples the flyer, and drops it into the nearest trash bin. But the phrase stays with him. He knows Semper means “always”—like the Semper Fi he sees on Marine bumper stickers. But eadem? Maybe he said déadem? Which, to Maslow, sounds like a precious jewel. Or slang for a mob killing. Dead-em

After looking up and down the sidewalk to make sure he won’t be interrupted by any other refugee from ye olde England, Maslow leans against a wall and pulls out his cell phone to look up eadem or déadem. It’s eadem. The literal translation is “always the same.” And it was the motto of Elizabeth I.

Maslow hears voices. Not the kind you hear in your head. The kind that are spoken clearly by people who aren’t there. Audio hallucinations. A surprising number of people have them; many of whom are considered delusional. Maslow isn’t delusional—at least in the traditional sense. It’s more like having strangers who stop by for a visit rather than shady specters who are up to no good. Usually they are historical characters. Sometimes they give him a sign that they are on their way.

Maslow begins to wait on the queen.

After a week, he begins to get impatient. So he reads a biography about Elizabeth, watches movies; listens to podcasts. He wonders why she waited so long to execute her Catholic cousin Mary Queen of Scots who was endlessly conspiring against her. He speculates, as historians have for centuries, on her virginity. He ponders the traumas of her early life—a beheaded mother, imprisonment in the tower of London by her sister, constant threats of assassination from inside and outside her land—and how they would have affected her personality and politics.

From time to time, he repeats semper eadem semper eadem to himself like a mantra or the incantation of a wizard.

But no Elizabeth.

Another week goes by. Novels. Films. Kids’ books. He pins a timeline of her life on a wall. A map of Elizabethan England next to it. A half dozen pictures of her at different ages. He tries to memorize her most famous quotes.

Her final word on the conflict between Catholics and Protestants: “There is only one Christ Jesus and one faith: the rest is a dispute about trifles.”

Her masterpiece of false modesty when exhorting her troops before they met the Spanish armada: “I know I have but the body of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too.”

And, perhaps the true key to her personality: “I observe and remain silent.”

But no Elizabeth.

*********

Maslow has a writing cabin behind his house. He does write there occasionally. But he also reads, throws darts, rides his stationery bike, does a little yoga or Pilates, drinks a lot of coffee, takes frequent naps, and sits on the screened porch and stares.

That’s what he’s doing today. Up in the treetops, all is as it should be. The oaks along the ridge are showing barely a bud, but the maples are well on their way to leafing. The poplars are just a few days behind. The narrow spread and subtle cross-hatching of their top branches gives them a human touch, like the faces that appear in clouds. On the left, he sees a scowling teenager. To the right, a droopy old man. In the center, however, is the woman he’s been waiting for, high above the others.

Her face is long and oval, with a firm, but jawless chin. Fine branches drift down like tears past forlorn eyes and a turned-down mouth that’s of a piece with those eyes. But the most distinctive feature of this particular figment is the hair—fine curls of what must be the tiniest twigs strewn across the forehead with one forming a kind of lock of hair in the center. A light breeze raises her eyebrows.

“Semper Eadem. Be Always ONE.”

Each word distinct. The last one loudest. But it’s not the literal translation, Maslow thinks.

“ONE.” She repeats.

Maslow holds his breath..

“You may breathe,” she says, a light-hearted parody of a royal command.

Maslow doesn’t dare speak.

“You may speak,” she chuckles.

Maslow feels the urge to get down on one knee and pledge his undying allegiance.

“You may rise,” she chuckles yet again, reading his intention. He’d often imagined how Elizabeth would speak. Authoritative, he assumed. Condescending, perhaps. Maybe a little amused from time to time. He did not expect her to chuckle.

“Now, record this, Our dear Scribe.”

The royal we. That he had expected. But scribe?

Maslow doesn’t want to take his eyes off her, but he needs a pencil and pad. He gets up from his chair as quietly as possible, goes inside, and tiptoes back out. He doesn’t want to break the spell.

“Still here!” She says brightly, adding a gust of wind for emphasis. The poplars wave wildly, like subjects obeying her every command.

“We begin.” She waits for him to put pen to paper. “Semper Eadem. Our guiding principle through multiple lifetimes. One mind. One heart. One spirit.”

This makes no sense, Maslow thinks. Elizabeth may have been powerful but she was anything but single-minded.

“You dare to question your Queen?”

While Maslow is often in awe of the voices, he has learned not to unconditionally surrender to their power or their perspectives. They may have history on their side but he has the here and now on his. “Elizabeth,” he says quietly but firmly, as if trying to disabuse a good friend of some strange notion: “Your courtships went on for decades; your death sentences were delayed time and time again; your relationships with foreign countries were all over the place…”

“Ah, but our poor dear insolent Scribe…I was not indecisive. I simply knew how to wait. Especially when even the slightest movement would fan the flames of discord that swirled relentlessly around our kingdom.

“The King of Spain wanted me dead—especially after I refused to marry him. The Queen of Scotland, my own dear cousin, prayed for my death, and schemed endlessly to bring it about. The Pope himself wanted me killed and even absolved in advance anyone who performed that blessed sacrament! All of them did so in the name of the dear loving Jesus whom they allegedly worshiped, but whose acquaintance they clearly never made.”

Now Maslow scribbles quickly. She no longer seems to be toying with him. She’s speaking her truth.

“When conflict arises,” she continues, “we look it straight in the eye. Otherwise, it festers like a cancer. Whether between countries, the people, the Court, lovers, or within oneself. To stay in the presence of conflict without flinching, without reaching for the weapon, without signing the order of execution, without agreeing to the proposal of marriage, takes real courage…and the sweet art of negotiation, of which I was a highly skilled practitioner. Because I could see into the hearts of men and women.

“So, when action was called for, I simply leaned. One way or the other. A little forward or back. Never losing my balance or, I must say, my head.

“Remember my words: ‘Men fight wars. Women win the peace.’”

Maslow does remember the words. A good turn of phrase he’d thought, but certainly, it’s not that simple.

“Men try to overcome. Women know how to undermine,” she adds, by way of explanation.

Also too simplistic, Maslow thinks. His mind races to find examples. “What about your Boudicca?” he asks. “Joan of Arc!”

“They lost,” Elizabeth says simply. “Their achievements are legendary. They won battles. That was their role. But they were defeated in war.”

Maslow is having trouble following. He’s not sure of her point. What did she do that was so special?

“Our dear Scribe.” Until now, Elizabeth has been proclaiming. Now she is scolding. “You’ll never enter our Kingdom through your mind. Listen to me now. Wrestle with my words later.”

“When it’s time for bold action,” she explains, “the queen knows it must be swift and unexpected—undermining rather than overcoming the other’s attack. Then we return immediately to the center of the hive.”

Maslow remembers Alma’s queens. Directing the hive through subtle shifts of energy. Her every need met by her attendants. Even when leading her loyal followers to a new home, she remains in the midst of the swarm.

“That’s right!” Elizabeth says it with light upward lilt of her voice, as if Maslow had figured out the first clue on a treasure hunt. “Then what?”

He remembers Alma saying that each hive has a different harmonic. Like two notes vibrating that let you hear a third. Even in a hive filled with thousands of whirring notes, there’s but one harmonic.

“Exactly,” Elizabeth says. “Our Scribe is finding his way. Now, attend to this, although you will likely barely glimpse its truth this lifetime. There’s no peace without war. No action without reaction. No power without weakness. No opposites, no harmonics. No harmonics, no evolution!” Her joy is contagious. The trees sway. Maslow starts to rock a little forward and back in time with her words, as if in prayer.

“On earth, Great Nature is the harmonic. In the hive and the kingdom, the Queen, herself, is the harmonic. In humans, Shin is the harmonic.”

Shin? Maslow wonders. The Tao?

“Words. Words. Words. Listen to the harmonics, our dear Scribe. There lie all the answers you seek. Follow the path of the harmonics. There goes the Way of the Universe. When heart and mind are ONE, there is creation.”

Maslow surrenders logic. Her words are dense. But he feels their meaning.

“Yes. Yes! Remember, we will not overcome or undermine you. We will only lean. We don’t want to lose you. That’s enough for now, our serious Scribe. Except…”

Then there is quiet. He looks up and stares at her tree, softening his eyes, hoping she’ll reappear. But she seems to have finished speaking.

Except what? He wonders.

Her voice returns: bawdy, raucous, a wench tossing propriety to the wind.

“Except for the burning question of our virginity that torments our poor befuddled Scribe and legions of historians before him. Only blessed Mother Mary’s has been debated with as much passion! And we assure you that is not a coincidence.” She follows with her signature chuckle. “We shall return. In due time…”

“Wait!!” Maslow shouts it out loud. Quickly tilting forward, he pushes himself to standing, clasping his hands behind his back, shifting his weight from foot-to-foot and looking straight ahead—as if she were the sun, daring him to look directly at her. Throwing shame and disbelief to the wind, Maslow feigns anger although he finds himself unable to feel it. “OK, OK, enough already! I’ve been lectured by rulers, composers, explorers, scientists, and philosophers. One time I was virtually seduced by a movie star! All of you deconstructing this, reconstructing that, as if you’re all on some mission from God to set humanity straight.”

“Yes,” she says it simply, acknowledging his summation but giving it no particular import.

“Well, who the hell is ‘You’ ‘We?’ Some royal you or a whole kingdom of ‘you’s’’? And what do you mean ‘the others’? How many of you are there? Why are you here? What are you all going to do? Lead billions of spirits on some new Crusade?”

“Who, the hell … is … we?” her tone a mild grandmotherly reproach for his language and grammar. “Ah, the Scribe tries to find his bearings. And still, he loses his balance.”

Maslow stands very still and tries not to blink.

“Well,” she says with a royal harrumph. “Truer than you think. Individuals only reincarnate to complete their individual aspects. We reincarnate to complete us all.”

“Aspects? What are aspects? You are the reincarnation of just Elizabeth…”

“Just? Just? Oh, you people. Always trying to fix us in time and space. So you can use us as exemplars and excuses for your petty opinions and ignorant ways. We are far more than Elizabeth. We were always far more than we appeared. And now we are far more than even that. As are all the others.”

Her strange thoughts and twisted logic make Maslow squint in frustration. And her fast-and-loose use of personal pronouns isn’t helping. Meanwhile, his whole body has started moving forward and back again, in time with some insistent rhythm.

She offers Maslow a meager lifeline, but keeps it taut: “Do you really think that when we die, we’re fixed for all time?”

“Well, not exactly.” “What do you think?”

Maslow takes a moment to close his eyes and regroup. It really is like he’s having an audience with a queen…and his future depends on giving the right answer.

“I think that when we die…” he speaks out loud, clearly, struggling to give his words the deep philosophical import they deserve… “the person we were lives on in memory and then, I guess, either the spirit reincarnates in a new body, or dissipates and blends with some primordial ooze which keeps sending us out in different forms.”

A good answer, he thinks. A very good answer. He braves a small smile and opens his eyes.

He’s talking to a tree.

© 2021 David Blistein

Waking the Dead

Marcus Aurelius

121 – 180 Roman Empire

Marcus Aurelius, the emperor of Rome from 161 to 180 AD is best known for his Meditations, a remarkable book that captures the essence of stoic philosophy, and is the equal of the Tao te Ching, Bhagavad Gita, Plato’s Republic, and other classic texts that struggle to establish the principles of ethical behavior.

“I see the same ceaseless chasing after vanity and pride that drove my people mad with power. I see the same exaltation in others’ suffering that made our coliseums roar with bloodlust. I see the same insistence on putting personal gain before common good that brought down the many with the few.”

Full Story Text

Marcus Aurelius

Maslow is taking an early morning ramble around the small New England college town where he grew up. He’s surrounded by students on their way to class. They seem impossibly young. But when he was a child, they seemed enviably mature. He yearned to be a member of their tribe, not just another faculty brat.

Every morning, Maslow would walk through the campus on his way to elementary school. The memories are visceral:

The students are on their way to class.

He’s on his way to third grade.

They carry thick textbooks under their arms or in green canvas bags.

He carries a spelling primer and a red plaid lunchbox.

They will soon be sitting around big tables, smoking cigarettes, and having deep conversations, maybe with his dad.

He’ll be chained to a tiny maple desk, wrestling with smudgy penmanship (the curse of all lefties), crayons that refuse to draw the pictures in his mind’s eye, and teachers who seem oblivious to the grown-up thoughts swirling inside his head.

After school, Maslow would often sit on the hill overlooking the practice fields, watching the lacrosse team scrimmage. The coach, a family friend, had found a kid-sized stick, and a few of the guys would toss the ball back and forth with him while they warmed up.

As he approaches that hill decades later, Maslow feels as if he’s walking in his own footsteps. He pauses before a familiar statue—a man riding a horse with its right front leg raised. The man holds the reins with his left hand while his right reaches out, palm down, not a single tremor—the commander of an invisible army about to swarm across the fields below. The statue’s distinctive gray-green coloring keeps Maslow shimmering between past and present. He used to puzzle over the inscription, wondering why the “U’s” were “V’s,”: Marcvs Avrelivs Antoninvs.

Now he knows that color is called verdigris…the patina of weathered bronze. Now he knows that the statue isn’t of just any old guy on a horse, it’s the Roman Emperor and brilliant stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius. Now he knows that it was not miraculously carved right on the spot, but is a casting—the original is in Rome. Now he knows that there were no capital “u’s” in the Roman alphabet. They used “V” instead.

Still, he has to wonder if the knowledge he’s gained is anywhere near as valuable as the curiosity he’s lost.

Maslow walks around the base of the statue, examining details of construction, balance, proportion, and light that he wouldn’t have noticed as a kid. Back then he wouldn’t have been able to look away from the immovable face of the emperor, and the nobility of his horse, perfectly poised in mid canter.

He wishes he had a cigarette even though he no longer smokes. He wishes he had a cup of coffee although he’s already had two. He wishes he had a pen and paper to write down the memories that are racing past his mind’s eye:

Like the time he ran down this hill so fast he face-planted at the bottom and ended up in the Emergency Room with a nosebleed that just wouldn’t quit. Or the time he walked here after school with his 6th grade girlfriend so she could watch him tossing a lacrosse ball with the big guys. Or when he smoked his first joint here a few years later, different girl, staring up at the stars, overwhelmed by deep insights into the mysteries of the universe.

“Steady. Steady yourself.” The voice comes from above him as if it’s commanding the horse.

Maslow looks around, but there’s nobody nearby. He didn’t expect there to be. An auditory hallucination. Unmistakable. As if spoken by someone right next to him. Not at all like a voice in his head. He hasn’t had one in years.

In Aurelius’s day he might have been considered an oracle. Today he might be considered mad.

“Doubt is truly a luxury you can ill afford.” The voice is rueful. A statement of fact. Not a warning.

Maslow stands by the side of the base and the familiar inscription—cool and gritty. His sense of time and space is growing increasingly fragile.

“Steady yourself…” the voice repeats.

Maslow takes a deep breath and looks around to get his bearings. The line of equally spaced trees that form an arc behind the statue? They were saplings when he was a kid. The statue’s long sunrise shadow stretching across the field below? Sometimes he’d race his friend Peter to the end of it on their way to school. The bell that just started ringing at College Hall? That means classes will end in five minutes, just as they had ended with five minutes left fifty years before. He’s marooned on timeless island in the midst of the here and now.

Maslow sits down on the pedestal and puts his head in his hands, hoping he looks more Socratic than psychotic. Aurelius comes into focus. They are sitting on their weary horses on the Palatine Hill at sunrise, surrounded by the mansions of Rome’s elite. Just back from another campaign against the barbarian warriors sweeping down from the north and east. They contemplate the proud temples, monuments, and endless porticoes of Aurelius’s falling empire, alone in the knowledge of just how fragile they are…and the cost of protecting them from their inevitable fate. To Maslow, it feels unspeakably tragic.

“No drama, my friend. It would be a distraction.”

Maslow no longer needs to suspend disbelief. The voice is simply stronger than his capacity to doubt.

“Good. We begin.”

Aurelius has the tonal range of an experienced orator—authoritative, but not pompous. And he’s talking not only to Maslow, but to the ages.

“Imagine as a young man you set out on a long journey, filled with dreams of mystery and adventure. You return years later. Wiser, more compassionate, eager to share your discoveries, curious to see how your city has changed. But nobody cares about your adventures. And nothing has changed at all.”

He sounds more wistful than bitter. Maslow feels an ancient scrim of sadness settle in his throat.

“Hold fast to your senses,” Aurelius insists, continuing: “At school, they teach the same subjects, in the same way, from the same texts. In the forum, they have the same arguments, about the same issues, with the same results. In the temples, they worship the same gods, with the same prayers, and the same intolerance for all who believe otherwise.”

The emperor lowers his voice to a sandy whisper: “So I gaze upon humanity today. The faces, costumes, weapons have changed. But the stories are all the same.”

Maslow sits up even straighter, making fine adjustments to the frequency so he can catch every word…and the ones not being said.

“I see the same ceaseless chasing after vanity and pride,” Aurelius continues, “that drove my people mad with power. I see the same exaltation in others’ suffering that made our coliseums roar with bloodlust. I see the same insistence on putting personal gain before common good that brought down the many with the few.”

The images cascade past Maslow’s inner eye as if it were as if it were his own life passing before him.

“Indeed, I see your world through the spectral remains of my own profound melancholia…”

The words trigger a vivid memory. Maslow is in his thirties, pulling Aurelius’s Meditations at destiny’s random from a bookcase. Wrapped around dark thoughts, irrational resentments, and sobering cognac, he is unceremoniously dragged from his brooding by the eloquent stoicism of this philosopher-king: “Let the harm done by another stay where the harm is done…” the historical Aurelius had written. And: “Men will keep doing the same things even if you burst in protest.”

“Yes. My words.” Aurelius acknowledges them with neither pride nor regret.

Maslow begins to nod his head and feels a tremor of anticipation and realization. The emperor’s words may still be brilliant and profound. But they are old. Aurelius is as stuck as the masses he has assailed for two thousand years. He has the same old complaints, the same old philosophy.

“Yes.” The emperor says it as if admitting to a crime he’s been waiting to be accused of. “That is why we are here. It is time to move on.”

“We?” Maslow asks. “Who’s we?” He speaks the words out loud and quickly looks up to see if anyone is listening.

But Aurelius is gone. A thread falling out of a needle that’s punctured another realm. Maslow waits. His mind starts speculating. So he opens his eyes and returns to the world he’s known since a child. Buildings of brick, stone, and marble. Geometric walkways. Perfectly tended lawns with patches worn brown by impromptu sports and spontaneous protests.

His senses have a long history with this campus. But now it looks very, very unfamiliar.

There’s no time to wonder how the water becomes wine. We drink it.

There’s no time to figure out why the seas have parted. We cross them.